Movie Review: Earwig and the Witch

Rated PG for some scary images and rude material

In recent years, Japan’s world-famous Studio Ghibli (home to films such as Spirited Away and My Neighbor Totoro), has quietly emerged back into the spotlight. While word circulated that co-founder Hayao Miyazaki has come out of retirement to work on a new film, there have been a few other artists who are producing films under the company’s name. One in particular is Hayao’s son, Goro.

Needless to say, Goro’s work for the studio has been somewhat of a mixed bag. His adaptation of Urusla Le Guin’s Tales From Earthsea is often ignored by some (and led to some bitter words from his father), while his sophomore effort From Up on Poppy Hill proved to be a rather enjoyable story about young people living in post-WWII Japan.

Now after almost a decade, Goro has returned to direct Earwig and the Witch, based on a story by Diana Wynne Jones (the author of Howl’s Moving Castle). Most notable about this production, is that it is the studio’s first where computer-generated imagery has been utilized to bring familiar character designs to life.

__________

Cute and manipulative orphan Earwig (Kokoro Hirasawa) enjoys her days at the St. Morwald’s Home for Children, where she revels in quietly lording over the place and a number of its people.

Things change when one day, she is adopted by a woman named Bella Yaga (Shinobu Terajima), and her lanky partner named Mandrake (Etsushi Toyokawa). Earwig soon finds out that these strange people are actually a witch and a demon, living in a house not far from the orphanage.

Though Bella simply wants Earwig to be a helper as she prepares spells and enchantments to pay the bills, the young girl is determined to learn magic and other powers from her new guardians, whether they like it or not.

__________

As soon as still images of the production were released, I was mildly apprehensive of the familiar Ghibli designs having been translated into the computer. Once I saw the characters in motion, it took some time to accept what was being done. There is definitely some care put into a rendering a lot of the familiar traits we’ve come to know for the studio’s character designs, but it feels like the animators tend to make some of the moves a bit more “floaty” than I would have expected, let alone the textures make the characters often look like plastic figurines. There are even a few areas where they had to compromise on translating some expressions, with one of the strangest being how they visualized the boisterous “Miyazaki laugh” many of us know.

Taking in the film as a whole, I found it hard at times to figure out just where the story was going. There are a number of times where it feels like we are getting little clues as to what may be coming down the pike, but they seldom seem to pan out.

A big element (and selling point of the ad materials), is that it seems Bella and Mandrake were once part of a band prior to the events in the film. One would have assumed that Earwig would have been pulled into this history lesson (she even shares the name of an album in Mandrake’s possession!), but the film doesn’t think this that important, making a few of the promo materials to feel misleading.

As a character, Earwig herself is one that is hard to really get behind, let alone see her as anything more than a little girl who is determined to make this new house bend to her will in a matter of time. Aside from her sneaking around the house and quietly griping at whatever Bella makes her do, there just aren’t a lot of quiet moments to really find much to make us care about her.

The same can be said for Bella Yaga and (the) Mandrake. They seem to have their own lives and things that they do, but the film just doesn’t want to take the time to explore this. We never do get to see Bella doing much outside of potion-making, and Mandrake just constantly gets fired up about one thing or another. It also stands to reason that Bella is not some wicked witch, given Earwig’s nice clothes and daily meals (though one could make a drinking game out of all the times Bella threatens to make Earwig “eat worms”).

The inability for the film to really go anywhere is its biggest downfall. Goro presents all these elements that make the viewer ready to find out more than Earwig just being stuck in the house, but he doesn’t do anything really compelling with these characters to push them out of their mundane lives. We’ve seen Hayao do some intriguing things with witches and demons in some of his films, but this film feels like if Sophie from Howl’s Moving Castle just never did much once she got to the castle.

The film also brings back a former collaborator, in the form of Satoshi Takebe. Unlike his more traditional score from Up On Poppy Hill, Satoshi adds some jazzy rock instrumentals at time that seem quite out-of-place from what we’ve had in the past. It adds an extra layer of darkness and intrigue to the film, but the music at times also slows down to the more familiar melodic tempos we’ve known from past films too.

At the start, I slowly began to get sucked into the story of Earwig and the Witch, as the character stylings began to seem palatable and the unusual use of rock music seemed to feel like this could be a grand experiment for Studio Ghibli. Sadly, the story just feels like there are a bunch of better plotlines that never go anywhere. As I looked back on the film, one of the most shocking things to me was just when the film felt like it might actually go somewhere interesting…it ended!

__________

Final Grade: C+

An Animated Dissection: Thoughts on “Porco Rosso,” 25 years later

In my Animated Dissection columns, I often strive to remember or make note of several films, that I often feel are worth discussing. Some can be well-known films, and some are those that have fallen by the wayside in favor of more popular pieces of work. There will also be some animated films that I just can’t stand…but fortunately, this one isn’t one of them!

Director Hayao Miyazaki may be known for some of his more popular films like My Neighbor Totoro and Princess Mononoke, but I have found that one of his more ‘subdued’ films, is one I have often found myself thinking about on several occasions.

__________

In the years following World War I, pilot Marco Pagot shied away from humanity, and became an anthropomorphic pig, assuming the moniker of Porco Rosso (aka “The Crimson Pig”).

Since then, he has used his piloting skills to become a freelance bounty hunter, flying across the Adriatic Sea, often encountering a number of colorful air pirates.

Porco Rosso (“The Crimson Pig”)

When not bounty hunting, Porco usually heads off to partake in fine wine and good women. Sometimes, he can also be found at the Hotel Adriano, owned by his childhood friend Gina, one of the last connections he has to ‘the old days.’

Things change for Porco, when his plane is badly shot-up by an American pilot named Donald Curtis. With the last of his funds, Porco heads to Milan, and makes contact with a mechanic he knows named Piccolo. For rebuilding the plane, Piccolo assigns his granddaughter Fio to the duties.

Porco is at first against this, but with all the men Piccolo employs away, he is out of options. Porco gives in, with the hopes that the young girl’s work can help him best Curtis, when they meet again.

__________

Hayao Adapts Himself

Sometimes, some of Studio Ghibli’s films directed by Miyazaki, tend to be ‘happy accidents.’ That was the case with Porco.

Originally meant to be a 45-minute feature that would run on Japanese Airlines flights, it was to be an adaptation of Miyazaki’s 15-page watercolor manga, titled The Age of the Flying Boat.

Top to Bottom: Panel from “The Age of the Flying Boat;” the same scene, as depicted in “Porco Rosso

The story is pretty simple, and one can see why it’s 3-part structure, may have been considered an easy piece to become a short feature for an in-flight movie.

Flying Boat serves as the underlying skeleton of the film, though one can definitely see differences in the pieces.

Notable is in the opening fight Porco has against some air pirates. In the manga, they kidnap a young woman, whereas in the film, the pirates kidnap a group of young schoolgirls, leading to a crazy romp as the pirates try to battle Porco in the air, and keep the rambunctious toddlers under control.

There also is the absence of Porco having a storied past, and Donald Curtis is known as Donald Chuck.

The end dogfight between Porco and Donald, also had to adhere to the limits of the printed page. Regarding the big battle, Miyazaki wrote: “If this were animation, I might be able to convey the grandeur of this life-or-death battle. But this is a comic. I have no choice but to rely on the imagination of you, good readers.”

It is notable that when pitching the film to the airlines, they were worried the aerial dogfights might get their proposal denied, but were surprised when the company said had no problems saying ‘yes’ to the material!

The multi-language opening of the film.

As production carried on, the animation and costs proved to be a bit more cumbersome than originally thought. That was when producer Toshio Suzuki, felt they should actually turn Porco into a theatrically released film.

Even though the deal for the film had been changed from it’s original intent, the airline still would be named as an investor in the film, and would still get to run Porco on their flights. Word is, the deal is the reason for the film’s unusual opening, where a number of little green pig-creatures (a design created by Hayao himself!), ‘type’ out a summary of the film, in several different languages.

The real-life Marco Pagot.

One could also assume that Miyazaki made up Porco’s human identity, but the name Marco Pagot is actually an homage to a real person Hayao knows (see picture on right)!

The two crossed paths when working on the anime series, Sherlock Hound, of which Pagot (an Italian animator) wrote a number of the episode’s scripts, and Miyazaki directed several of the episodes. Word is that Marco’s wife Gi, may have also inspired the naming of Porco’s friend, Gina.

__________

A Different Kind of Anime

Compared to the other films Miyazaki has directed, Porco is the only film of his where it’s lead is not a young individual. Instead, Porco is a person who was once an optimist, until war and the world disillusioned him, turning him into the ‘creature’ we see.

Some could almost see the film as being in the same vein as Herge’s Tintin comics, or even Steven Spielberg and George Lucas’ Raiders of the Lost Ark, in how it intermingles action, drama, and at times, comedy.

Porco at times, sounds a bit like how George Lucas originally envisioned Indiana Jones, where the professor of archaeology would be a dashing playboy when he wasn’t off searching for lost relics. Though much like how we saw Indy portrayed in his series of films, we are never privy to Porco’s ‘flings,’ and simply follow him through his sea-based adventures.

Though Porco makes an okay living, it should be noted that a number of air pirates we see, are just as hard-up for funds as he is. When the Mamma Aiuto gang loses the tail on their plane due to a dogfight with Porco, their finances are only able to get them a replacement tail (see picture on right), but not enough money to even paint it, making it’s silvery form stick out like a sore thumb.

Though Porco makes an okay living, it should be noted that a number of air pirates we see, are just as hard-up for funds as he is. When the Mamma Aiuto gang loses the tail on their plane due to a dogfight with Porco, their finances are only able to get them a replacement tail (see picture on right), but not enough money to even paint it, making it’s silvery form stick out like a sore thumb.

Porco himself is also one of the quieter leads that Miyazaki had written up to that point. Often observant and contemplative, he probably speaks the least of all the main characters the director has had. However, it is rather interesting to see how much expression Miyazaki’s animators get out of the minimal movements he has. Plus, for the majority of the film, his eyes are hidden behind the dark shades of his glasses.

Much like how real-world events shaped the work being done on Howl’s Moving Castle’ almost a decade later, events in the area during the 90’s, where the film was taking place, influenced it’s storyline.

When Yugoslavia broke up in the early 90’s, this added an extra tinge of ‘reality’ to the film. Whereas the rise of fascism across the Adriatic in Flying Boat was only hinted at in the adapted manga, we get a small taste of what’s going on in the film, when Porco comes ashore to Dubrovnik.

Paying off the loan on his plane, the bank employee tries to get him to purchase war bonds, but he simply responds that that is something the “humans” can do.

After this, he visits a small shop to pick up some more weaponry and ammunition. Word of a governmental change is on the mouths of several of the shop’s workers, but Porco claims he has no intention to fight in another war.

Porco at the Ghibli Museum.

Also of great interest, is the ‘curse’ surrounding his transformation into a pig-headed man. After all these years, Miyazaki has never given an explanation for the ‘curse,’ often leaving the mystery to the audience, to unravel in their own minds.

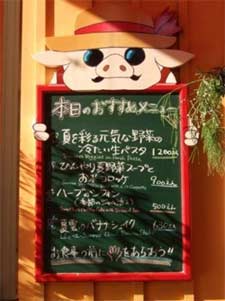

Even the face of Porco with his dark glasses, is an image that Miyazaki likes to ‘doodle,’ just as much as his imagery of Totoro. Porco even shows up at the Ghibli Museum’s cafe in Mitaka, Japan. Known as the Straw Hat Cafe, Porco’s head appears over the cafe’s chalkboard menu, but instead of his aviation goggles, he wears a straw hat.

__________

Women in Control

With his previous features, Miyazaki largely focused on female leads. From Nausicaa to Kiki, his girls and women often found their optimism tested in the face of adversity, or events that were oftentimes foreign to them.

Though Porco is our lead for this film, Miyazaki makes sure that the girls and women that we see around him, are often some of the more level-headed characters.

Of those we see, the characters of Gina and Fio act as a sort of yin-yang

Gina was a former childhood friend of Porco’s, and was married to one of their friends. However, when we see Gina, she is a widow, entertaining and running her hotel in the Adriatic Sea. She is self-sufficient, and though it seems she may pine for Porco at times, she is not one to just run off with any man.

This is notable when Donald Curtis finds her in her garden, and in a rather extravagant, “American” way, proposes to her…which leads to Gina laughing heartily, as she hears him claim that he intends to become President one day!

While Gina is the older woman who has lived life and matured, Fio is the young girl, the optimist with unending energy, that often overpowers some of Porco’s own misgivings.

Notable is when Piccolo declares that she will be doing the new design work on Porco’s plane. Porco is at first against this, but she manages to convince him with her enthusiasm, as well as her ‘plussing’ Porco’s plane. Much like the disconnect between some generations, Porco doesn’t wholly understand a lot of what Fio is doing to his plane, but he trusts her enough to figure that the alterations she pushes him to approve, are going to help him out in the long run.

Another notable scene comes later on, when Fio and Porco encounter the air pirates, who first intend to destroy Porco’s rebuilt plane, until Fio reminds them of the honor of being ‘flying boat pilots.’

Women also become the only workforce available to Porco and Piccolo, as a number of men have left Milan because of the Great Depression, leaving Piccolo’s relations to carry on the rebuilding effort.

__________

Beautiful Imagery

Several of Miyazaki’s works reference Europe, and the locales of this film, play out in such a way, that a few of it’s panoramic landscapes may get stuck in your head.

Most notable to me, is one where Porco decides to head off to Milan. as a Mandolin strums a melody, we see the red plane, but far away, as an enormous mass of clouds seems to dwarf it!

The film at times seems to act as an eye-opening travelogue to the Adriatic, given all the scenery we visit. Even Porco’s island hideaway looks like the perfect place to get some peace and quiet.

One of the film’s more ethereal moments, comes when Porco tells of a near-death experience he had, near the end of the first World War.

Seeing a streak of white high in the air, it soon turned out that it was a ‘stream’ of planes, (thousands of them!), and of which Porco soon saw his comrades who had perished in a recent aerial battle, rise to become a part of!

The scene is one of those that seems to ‘haunt’ my memories. It is a vision I have never seen committed to film before: the sight of numerous vintage aircraft, flying in a neverending stream. Are they going somewhere? Are they cursed to forever circle above us, never to be seen? We’ll never know.

__________

An Ode to older animation

While the Ghibli style is present in this film. it should be noted that it seems the animation stylings of the time, can be glimpsed in a few places.

Most noticeable is in a black-and-white cartoon Porco sees, under cover of talking with a former Italian Air Force comrade.

The short seems to combine a number of different animation stylings, with it’s characters first seen flying in planes, which may be a reference to the first Mickey Mouse short, Plane Crazy. It’s lead characters seem to be a sort of loose-limbed rabbit character, and a large pig who attempts to abduct the heroine. This could also be some form of homage to Mickey Mouse, and his first nemesis, Peg-Leg Pete.

The heroine of the short, appears to be an amalgamation of Fleischer Studios’ depictions of Olive Oyl from their Popeye shorts, as well as with her ‘glamorous’ facial features, a mix of Betty Boop.

The leader of the Mamma Aiuto gang also may be influenced by Popeye, with his buff physique and spiky beard, he bears a passing resemblance to Popeye’s nemesis, Bluto.

It could also be said that the final fight between Curtis and Porco, may also be a small homage to the rock-em/sock-em fights that took place between Popeye and Bluto.

__________

Music of a Bygone Era

When it comes to music, Jo Hisaishi’s score for Porco, is one of the more journey-filled pieces he’s done for his friend’s films.

For the Mamma Aiuto gang and some of the other air pirates, Hisaishi breaks out the brass instruments, making it sound like most of what they are doing, is little more than an ‘aerial circus.’

When the action ramps up, so do the strings, and even at times, the woodwinds. A notable piece is when Porco and Fio escape Milan, as the Italian authorities attempt to apprehend him. It’s a tense scene of escaping through the city’s waterways, with a Shostakovich-like piano melody that plays over the scene.

Throughout the film, a mixture of piano and strings often punctuates Porco’s quieter moments, a trace of wistful melancholy flowing through some scenes. A piece dealing with Porco and Gina sharing time at her hotel, also has the faintest hints of the song “As Time Goes By” to it, as if the composer tried to throw in a little homage to Casablanca.

Fio also gets a theme, with woodwinds being the major motif. Her piece is a bit more ‘playful,’ and often enhances a number of scenes where the focus shifts to her.

Notable to me, is the closing song for the film, titled Once in Awhile, Talk of the Old Days. The track has a wistful melody, starting and ending with piano, before eventually building to a plateau with a number of strings, sounding like wind skimming across the mists of time.

I recall going back to my hometown in Iowa 9 years ago for my high school reunion, and the song seemed to sum up my feelings, seeing people I last remembered as teenagers, back when the world seemed more optimistic. The track played in my ears, as the bus took me out of a place I could recall more wistfully from youth, but had changed over time.

That seems to largely be the theme of Hisaishi’s overall score: music that feels like you’re looking back on a time and place. The memories are there, but it’s all a bit hazy from the decades that have passed.

__________

When one compares Porco Rosso to some of Miyazaki’s more ‘popular’ works, it often seems to easily get lost in the shuffle. Personally, I often feel that I and a select few people, are the only ones who have some love for the film.

One of the things that is most notable, is that it is one of Miyazaki’s shortest films, but the pacing of the film is so good, that it often feels like it is over too soon! I can’t recall ever being bored once during the entire film.

In researching this blog post, I was looking for further information in regards to Miyazaki’s remembrances, or comments following the release of the film.

Unlike some directors who seem to have fond memories of previous films, Miyazaki rarely seems to gush or hold any of his past works in high praise. This is notable in watching the documentary, In the Kingdoms of Dreams and Madness. One of the women in the documentary makes references to Kiki’s Delivery Service, as well as Porco Rosso. Porco is brought up, given that the film that was being worked on at the time (titled, The Wind Rises), also deals with flying machines.

However, when he remembers his older work, Miyazaki merely calls it “a foolish film.”

An interview for Animerica Magazine in 1993, also had him feeling that the film flew in the face of his feelings, that (in his own words), “animation is for children.”

It should be noted that a few years ago, rumor surfaced of a possible sequel to the film. Studio Ghibli is not a studio known for sequelizing, so this news was met with some caution.

A rumored title was Porco Rosso: The Last Sortie, and would have featured Porco taking to the air once again, this time as an aged pilot, during the Spanish Civil War.

No concept art or anything more was ever shown of this, and with the current status of Studio Ghibli seemingly closed off from doing anything other than an upcoming film project with Miyazaki, it is possible that The Last Sortie may join the ranks of many other projects the famed animation director considered, but never worked on.

Personally, I found the end of Porco Rosso had a decent closure to it’s story. Some loose ends were tied up, but other mysteries remained, for one of Hayao Miyazaki’s pieces, that feels like a good memory, I often enjoy coming back to.

Pretty good work for a film that was originally meant to play to weary businessmen.

__________

“Porco Rosso is a product of the early ’90s, of my world views being challenged by real-world events. It’s also the product of my resolve to overcome the challenge and build a stronger way of life, a stronger way of looking at things.” – Hayao Miyazaki, from an interview conducted by Takashi Oshiguchi in 1993, for Animerica Magazine)

__________

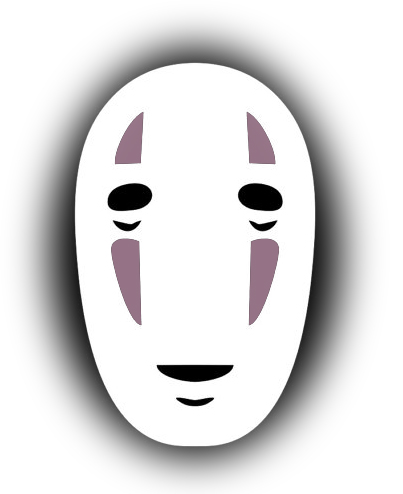

An Animated Dissection: The Growth of “Spirited Away’s” Bou

Even after 15 years, I feel there’s still plenty of things to find in Hayao Miyazaki’s Spirited Away. At the time of its release, it quickly gained fame for being the first film to unseat James Cameron’s Titanic from the top of the Japanese box-office heap (and it’s held that distinction ever since!).

When I saw the film for the first time, I was mesmerized at all the twists and turns that were presented! This wasn’t a ‘safe’ animated feature, but one where you truly felt that the lead character Chihiro, could very well find herself trapped forever in this other-world.

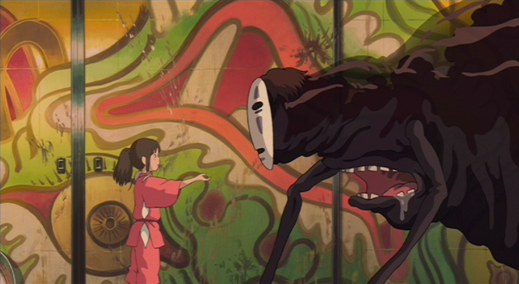

My observations on the film’s enigmatic No-Face have been one of my most-read blog postings, but it seems that almost every character in the film could be put under the microscope. Today, I decided to look at one of the film’s biggest characters, and how meeting with Chihiro, changed him.

__________

Once the film’s focus shifts to the Spirit World, Chihiro’s journey surely reminded many Western minds of similar journeys, such as Alice’s adventures in Wonderland, or Dorothy’s to the land of Oz.

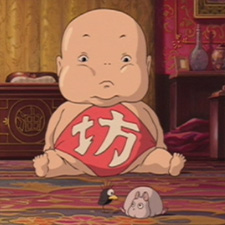

One of the more shocking moments in Spirited, comes when Chihiro and Yubaba get into a shouting match as Chihiro demands she have a job. Suddenly, the room is shaken, before a loud cry is heard. Following this, we see a door splinter, as a giant infant’s foot pushes through it! Yubaba rushes to the shattered doorway, and unseen by us, tells someone to be quiet, raising her voice in a ‘sweet’ tone to whomever she’s talking to.

One of the more shocking moments in Spirited, comes when Chihiro and Yubaba get into a shouting match as Chihiro demands she have a job. Suddenly, the room is shaken, before a loud cry is heard. Following this, we see a door splinter, as a giant infant’s foot pushes through it! Yubaba rushes to the shattered doorway, and unseen by us, tells someone to be quiet, raising her voice in a ‘sweet’ tone to whomever she’s talking to.

A few days later, Chihiro finds herself in the other room, which is a giant nursery for Yubaba’s baby, Bou. Though he is a human-sized infant, Bou can reason and speak.

After Chihiro hides from Yubaba under some pillows, Bou grabs her arm, demanding she stay in the nursery and play with him. Bou explains that his Mother says that there are germs and things outside of the nursery that will make him sick, which is countered by Chihiro, claiming that staying where he is and doing nothing will make him sick as well.

After Chihiro hides from Yubaba under some pillows, Bou grabs her arm, demanding she stay in the nursery and play with him. Bou explains that his Mother says that there are germs and things outside of the nursery that will make him sick, which is countered by Chihiro, claiming that staying where he is and doing nothing will make him sick as well.

She attempts to leave, but Bou threatens to break her arm, and alert his Mother if she doesn’t play with him. Chihiro manages to scare him, showing some blood on her hands.

After throwing a noisy tantrum, Bou follows Chihiro out into the main room, where he once again demands that she play with him, or he’ll start crying. As he starts working up some tears, a little paper ‘bird’ that had followed Chihiro, emerges from behind her. It addresses Bou, telling him to be quiet, and calling him a rather ‘rotund-like’ name.

As everyone watches, a transparent figure emerges from the paper bird, resembling Yubaba (and even Bou calls it by his Mother’s name). The figure then chastises Bou for confusing it with his Mother, before sending a wisp of magic at him, shrinking Bou down into the shape of a portly mouse. It also changes the other denizens of Yubaba’s office around, turning her Yu-bird into a little crow-fly, and her three hopping heads, into a recreation of Bou.

As everyone watches, a transparent figure emerges from the paper bird, resembling Yubaba (and even Bou calls it by his Mother’s name). The figure then chastises Bou for confusing it with his Mother, before sending a wisp of magic at him, shrinking Bou down into the shape of a portly mouse. It also changes the other denizens of Yubaba’s office around, turning her Yu-bird into a little crow-fly, and her three hopping heads, into a recreation of Bou.

Shortly afterwards, the three heads take advantage of their new body, and start trying to squash the mouse-sized Bou. Luckily, he and the Yu-bird manage to get away, clambering onto Chihiro’s shoulder for safety.

The moment takes a shocking turn when Chihiro, Haku, and the two little creatures fall down a pit that Yubaba’s three heads had been trying to push Haku down mere moments ago! In the descent, the Yu-bird attempts to keep Bou aloft, before Chihiro cradles them in her hand, as the descent quickly becomes a wild ride!

The moment takes a shocking turn when Chihiro, Haku, and the two little creatures fall down a pit that Yubaba’s three heads had been trying to push Haku down mere moments ago! In the descent, the Yu-bird attempts to keep Bou aloft, before Chihiro cradles them in her hand, as the descent quickly becomes a wild ride!

The journey ends when the group crashes into the bathhouse’s boiler room, where Chihiro manages to purge a strange black slug from deep within Haku. In a rather gross moment, she ends up squashing the creature under her foot, leaving a black smudge on the boiler room floor. She freaks out at what she’s done, before the boiler room’s caretaker Kamaji, demands she put her thumbs and forefingers together, and ‘breaking’ them with his hand, declaring the bad luck she has received from killing the slug, is now lifted.

As Chihiro and Kamaji tend to Haku, Bou and the Yu-bird have been watching the little Soot Sprites gathering around the blackened footprint where the slug once was. Bou goes over, and wandering into the center of the group, re-enacts what Chihiro did. After the ‘cleansing’ move (with one of the soot-sprites acting as Kamaji), Bou raises his paws in the air in triumph, and the little creatures cheer!

The little Sprites delight in the game, but when Chihiro calls them to help her, they quickly abandon Bou, who seems a little sad that his pretend-fame was fleeting.

When next Bou figures into the story, is when Yubaba confronts Chihiro, to take care of No Face. However, the conversation is interrupted when the little Yu-bird lifts Bou before her face, with him giving a little ‘Chu!’ sound, and wiggling his ears.

Obviously, Bou is greeting his Mother in his mouse form, but she just wonders why Chihiro has this ‘ugly mouse’ with her. Chihiro is surprised that Yubaba doesn’t recognize her son in this form, and even Bou is hurt by this, first appearing sad, and then scowling at his Mother.

Obviously, Bou is greeting his Mother in his mouse form, but she just wonders why Chihiro has this ‘ugly mouse’ with her. Chihiro is surprised that Yubaba doesn’t recognize her son in this form, and even Bou is hurt by this, first appearing sad, and then scowling at his Mother.

It’s rather low-key compared to the main story regarding Chihiro, but since his introduction, Bou has slowly been developing as a character. He’s a lot more mobile than before, and he has obviously gotten over his fear of germs, shown by his stepping in the remains of the slug. Though that was pretend-heroism, he gets a chance to shine when it looks like No Face may try to take, and consume Chihiro.

Just when it looks like No Face is going to envelop her head with his outstretched hand, Bou jumps forward, chomping into it! This causes No Face to stop, and attempt to swat the pesky rodent, before the Yu-bird picks up Bou, and returns him to Chihiro’s shoulder. It is Bou’s chance to be a hero on his own merits (albeit small ones), and not requesting glory for it.

Soon after, Bou and the Yu-bird make their way outside of the bathhouse, following Chihiro. We see Bou grow curious at a little bug that clings to the side of a train platform, as well as see his attention being drawn out the window of the train-car, as Chihiro and her companions head to Swamp Bottom, where Yubaba’s twin-sister Zeniiba resides. This is all new to him: the immensity of the Spirit World, must surely pale in comparison to the confining nursery he’s largely known throughout his life. Plus, the immensity of the world at his smaller size, must make his journey an even bigger event in his young mind.

Soon after, Bou and the Yu-bird make their way outside of the bathhouse, following Chihiro. We see Bou grow curious at a little bug that clings to the side of a train platform, as well as see his attention being drawn out the window of the train-car, as Chihiro and her companions head to Swamp Bottom, where Yubaba’s twin-sister Zeniiba resides. This is all new to him: the immensity of the Spirit World, must surely pale in comparison to the confining nursery he’s largely known throughout his life. Plus, the immensity of the world at his smaller size, must make his journey an even bigger event in his young mind.

Bou soon after shows another example of selflessness (following his ‘saving’ Chihiro from being consumed by No-Face some time ago). When the group finally gets to Swamp Bottom, the little Yu-bird finally begins to tire of carrying the little mouse around.

Bou soon after shows another example of selflessness (following his ‘saving’ Chihiro from being consumed by No-Face some time ago). When the group finally gets to Swamp Bottom, the little Yu-bird finally begins to tire of carrying the little mouse around.

After landing on the ground, Bou thinks for a moment, and then begins to walk on his own, carrying the tired little creature without any prompting. Chihiro even offers to put him on her shoulder again, but Bou refuses the offer.

Once the group finally gets to Zeniiba’s place, Chihiro asks her to change Bou and the Yu-bird back to their original forms. Zeniiba informs the two that the spell they were put under can be undone if the changed persons wish to change back. However, both Bou and the Yu-bird refuse (for the moment).

From here on in, Bou takes advantage of his little size, getting some exercise (and spinning thread) on Zeniiba’s spinning wheel, as well as snacking on the cookies she has put out for her guests.

After this, Bou is even seen learning how to knit, as Zeniiba coaches him and No Face. In fact, some of his new-found skills went into the new headband that Zeniiba presents to Chihiro, with the old woman claiming it is a gift made possible through her new friends.

When it is finally time for everyone to leave, Zeniiba addresses Bou and the Yu-bird, happily requesting they visit her again. Bou actually makes contact with his Aunt, kissing her on the nose (“Chu!”), and waving as the Yu-bird carries him away.

When it is finally time for everyone to leave, Zeniiba addresses Bou and the Yu-bird, happily requesting they visit her again. Bou actually makes contact with his Aunt, kissing her on the nose (“Chu!”), and waving as the Yu-bird carries him away.

Upon returning to the bathhouse, Bou returns to his previous form. Yubaba is surprised that her child is able to stand on his own, but grows even more surprised when Bou chastises her plans to test Chihiro.

Bou speaks positively of his journey, claiming he had fun. Even though Yubaba tells Bou that the test is part of how their world works, he shocks her when he says he won’t like her anymore, if she makes Sen cry.

Bou speaks positively of his journey, claiming he had fun. Even though Yubaba tells Bou that the test is part of how their world works, he shocks her when he says he won’t like her anymore, if she makes Sen cry.

His being vocal towards his mother regarding caring about another’s feelings, is a great example of showing how much Bou has matured.

One has to wonder if after this, his baby-ish ways we saw in the beginning of the film, are now a thing of the past. Though he does have a baby’s body, surely what he has been through, may very well shape him into not becoming greedy or arrogant like his mother.

It should also be noted that on a smaller level, the Yu-bird does not change back to its previous form. Maybe like Bou, it too has grown to understand a few things, and may no longer be a spy and lackey to the bathhouse owner.

__________

And thus, another Animated Dissection regarding Spirited Away has come to a close. Though like I explained earlier, there are still other characters and themes to examine. I wonder what I’ll cover next?

Movie Review: When Marnie Was There

(Rated PG for thematic elements and smoking)

With the announcement in 2013 that Studio Ghibli’s co-founders Hayao Miyazaki, and Isao Takahata, were releasing their final animated features, many film fans were thrown into turmoil. The same uneasiness was felt when rumor quickly spread that their swansongs, would mean the end of the famed studio as well.

Co-founder Toshio Suzuki (a producer on numerous Ghibli films) quickly put the rumor to rest, claiming the studio would focus on smaller-scale projects instead. While this allowed some to breathe a sigh of relief, this meant sadness for many beyond the realms of Japan. After all, to many of us out there, the films from Studio Ghibli were what reached our shores (most of the time).

Some would have figured that Isao Takahata’s The Tale of Princess Kaguya would be the final film released, but it turned out, there was one more left.

__________

In the summer of 2014, Ghibli released their ‘final’ animated feature, When Marnie Was There. Based on the novel by Joan G Robinson (though the setting has been moved to Japan), the film follows 12-year-old Anna Sasaki (Takatsuki Sara). After an asthma attack, her mother Yoriko (Matsushima Nanako) sends her off to stay with her Uncle and Aunt in a small town near the sea, claiming the air will do her good.

After exploring the seaside town, Anna’s attention is drawn to an elaborate structure on the far side of the village, that the locals call The Marsh House. One evening, Anna goes exploring there, and is surprised to run across a blonde-haired girl named Marnie (Kasumi Arimura).

Of the many different main characters explored in Ghibli films regarding children or teenagers, Anna is quite drastic, being very quiet, and somewhat “expressionless.” One assumes that maybe she is this way due to her asthma, but it seems she may have some emotions bottled up inside. Her mother explains to a doctor that Anna used to be very happy, but seems to have become withdrawn, rarely speaking to anyone.

One of Anna’s outlets is her sketchpad, in which she often draws, but seldom shows others. I was rather pleased to see another artistic teenager in a Ghibli film, one of the first since 1995’s Whisper of the Heart. Anna seems to cope better with just drawing, fancying herself an observer on “the outside,” rather than wanting to be someone on “the inside” of life.

Even though those around her largely try to be polite and enthused towards her, Anna seems to rarely give in. This seems a little odd, when she seems willing to give in and meet with Marnie, who seems so lively and boisterous. As well, Marnie at times tends to get pretty ‘close’ to Anna. I saw the film in a theater of only 5 people, and it made me wonder how a larger audience would have reacted to some of these moments.

After the more original stylings of The Tale of Princess Kaguya, it was welcoming to find myself back in the “normal” world of Studio Ghibli. The greenery feels welcoming, and the style of the characters doesn’t differ that far from the styles we know (the characters still cry like they sprung a leak, too). One thing I became entranced by, were single strands of hair that stood out from Marnie’s main mass of hair. It’s a little touch, but it tended to make her seem more ‘lively.’

Marnie as a film, definitely feels ‘different.’ Much like Goro Miyazaki’s film From Up On Poppy Hill, it seems moreso enamored with trying to make the ‘magic’ moments seem more natural, and not as elevated into the realms that Hayao or Isao would have gone to.

This is a film that almost feels like the newer generation attempting to get its feet wet, but I could see how the story could leave some feeling a little ‘flat’ in the end. Anna’s largely ‘blank’ expressions quickly put me in mind of the enigmatic-looking Jiro Horikoshi from Miyazaki’s The Wind Rises. Though luckily, Anna doesn’t hold her stoicism as long.

Much like Hayao Miyazaki has his themes, it seems that director Tomomi Mochizuki has his as well. The director of 2010’s The Secret World of Arrietty, one can find some story parallels to that film, and this one (an ill young person, sent away to a place where strange encounters may await, for example). With Arrietty, Tomomi had a guiding hand in Miyazak-san, but here, he’s been left largely to his own devices.

One of the highlights of the film, is the wonderful score by Takatsugu Muramatsu. Before I knew it, I was swept up in the melodies that wafted over the seaside town, as Anna and Marnie made a connection. As well, the closing song by Priscilla Ahn encapsulates the film so well. Titled Fine On The Outside, it feels like a song that many would be able to relate to.

__________

In the end, I was surprised to find that while I had fallen in love with the music and visuals of When Marnie Was There, I had not been swept up in the film’s most important part (to me): its story. Even thinking back to films like From Up On Poppy Hill and The Secret World of Arrietty, those films managed to entrance me with their characters, let-alone the stories they were telling.

This film could possibly have been Tomomi Mochizuki’s attempts to steer into new territory for Studio Ghibli, but I think many like myself, feel that you still need to give us some more investment in the characters. As well, the structure of some scenes left me scratching my head a few times.

The feelings I had reminded me of how I felt about the recently-released film, Tomorrowland, in which like Marnie, the visuals and music stuck in my head, but the story just didn’t tug at my heartstrings.

Though I have wondered now, some time after seeing it once, what I’d think of it if I had to watch it again. This could be like some films where the first impression may take on new meanings upon repeat viewings. Even so, my first impression of When Marnie Was There, turned out to fall short of my expectations. There seems to be an emotional sterility with the film much like with The Wind Rises, making me long for the emotionally affective levels that I experienced with Isao Takahata’s The Tale of Princess Kaguya.

Final Grade: B (Final Thoughts: The final ‘film’ from Studio Ghibli, showcases a story without its grand masters. Though skillfully crafted, it often feels too distant to ever let us get close to feel its emotional core. Even so, it shouldn’t be missed for the painterly environments and melodic score, that give us faint hints of a time that may very well be long past)

An Animated Dissection: Howl’s Moving Castle, Part 3 – The Witch of the Waste accepts who she is

Though Howl and Sophie are the main leads of Hayao Miyazaki’s film Howl’s Moving Castle, another character who is just as integral to the storyline, is The Witch of the Waste. One theme throughout the entire film, is how every other character has a false front regarding just who they are, and by the end, they have shed these fake personas, and come out stronger, and more accepting over who/what they are.

Of course, Miyazaki took many liberties with the characters from Diana Wynne Jones’ story, and the Witch of the Waste is no exception. Much of her involvement with our main characters does not follow the storyline of Jones’ book. Instead, Miyazaki chose to make her a character of age, vanity, and superficiality.

__________

Much like Howl seems to be close to the village where Sophie lives, there is rumor that the Witch of the Waste is nearby. During her first appearance, she stays hidden within the walls of a small, ornate litter. She is usually accompanied by several ‘blob men,’ who wear brightly-colored clothing and masks. Amazingly enough, no one in the village seems to notice these strange, tall, featureless ‘men.’

When we get our first full look at the Witch of the Waste, she definitely looks a little ‘off’.’ She has the appearance of an older woman, somewhat full-bodied. However, her body looks almost ‘sculpted,’ given that she seems to have a protuberance of neck-flesh under her face.

We can assume she tracked Sophie down, after her blob-men attempted to get Howl on the street in an earlier scene, and reported back as to who she was.

“What a tacky shop,” the Witch says, surveying the room. “I’ve never seen such tacky little hats. Yet you are by far, the tackiest thing here.”

Sophie doesn’t take well to being insulted, and orders this strange woman to leave.

When she leaves, The Witch of the Waste passes through Sophie, casting her aging spell on her. One might wonder why she would do this, but she probably figures that since Howl likes young, beautiful women, aging Sophie into an old woman will put him off her.

The Witch of the Waste then disappears for a good portion of the film after this, but her presence is never far from Howl, or Sophie.

After being taken in by Howl, Sophie finds a red note in the pocket of her dress (most likely placed there when the Witch passed through Sophie). It burns a symbol into a wood table in Howl’s castle, with an ominous message:

“You who swallowed a falling star, o’ heartless man, your heart shall soon belong to me.”

Sophie later asks Howl about this, and his association with the Witch of the Waste. Howl claims that he pursued her when he thought she was beautiful. But upon finding out her true form, he ran away. Since then, the Witch of the Waste has been pursuing Howl, trying to ‘recapture’ his heart.

The next time we see The Witch, is when Sophie goes to have an audience with Madame Suliman, the Royal Sorcerer from one of the kingdom’s requesting Howl’s assistance in the current war ravaging the lands. Though Sophie is there to speak on behalf of Howl, the Witch has chosen to personally appear per the royal invite she received from Suliman.

The Witch seems rather pleased to see Sophie, and delighted when Sophie relays that “Howl’s treating her like a house-servant.” When Sophie requests the Witch remove the spell on her, the Witch then explains an intriguing conundrum: though she can cast spells, that doesn’t mean she knows how to cure them.

However, from the moment she steps onto the castle’s grounds, The Witch of the Waste’s demeanor and spirit are tested. Her ‘blob men’ handlers are disabled, and she is required to complete the rest of her journey to meet Madame Suliman, on foot. This then leads to a scene of her and Sophie climbing a large number of stairs. While Sophie is slightly winded by the climb, the Witch of the Waste is even more strained by the ordeal.

Once she gets to the top, her statuesque form becomes stooped, her hair ragged, and the amount of ‘skin’ around her neck area appears to have loosened. In a funny turn-of-events, Sophie enters without the cane she came to the castle with, which has been given to the Witch.

While Sophie is led off to meet with Suliman first, the Witch finds a room with a chair in the center. Looking for relief from her strains, she rushes to it, and breathes a sigh of relief. However, the silence is short-lived, as suddenly a number of large lightbulbs are revealed, and switched on.

The room it turns out, is actually one that the Kingdom uses to gain control of witches and wizards. The room pulls their magic from their bodies, and in their weakened state, it is assumed that they will be persuaded to join with the Kingdom.

With the majority of her powers gone, the Witch’s true age is revealed, imperfections can be seen, and her eyes have taken on a glassy sheen, as seen when she is brought before Madame Suliman, and Sophie.

“There was a time when she, too, was a magnificent sorcerer with so much promise,” Suliman explains to Sophie, “But then she fell prey to a demon of greed who slowly consumed her, body and soul.”

As to who or what this demon is/was, it is never said, but one has to wonder if in some way, it was similar to the effects of what Calcifer had on Howl. Though both Howl and the Witch have very strong magical powers, they have chosen to use them for their own personal (selfish?) purposes. Maybe it could be Suliman claiming the human quality of “vanity” could be that demon?

One has to assume that somewhere in her life, the Witch of the Waste probably began to grow afraid of her age, and when it seemed magic was the only saving grace to the effects of age on her appearance and body, she looked inwardly, and used what powers she had on herself.

We often see this quality in humanity as well. Millions of dollars spent on trying to hide crow’s feet, sagging flesh, and thinning cheeklines. Every other story I pass, it seems there’s some treatment/solution offered, to keep one looking young and invigorated, so they’ll be noticed and attractive to a world that seemingly sees these signs of aging, as ‘deformities.’

The effects of the draining of the Witch of the Waste’s magic has also seemed to age her mind as well. She is quiet after the draining of her powers, but comes out of this ‘fog’ to say a few things, whether latching onto Sophie’s talk about Howl (“I want his heart! It belongs to me!”), or when her attention is drawn by some little things (“what a pretty fire.”). It’s almost like she is in some stages of Alzheimer’s disease, as her memories and coherency seem to come-and-go as the film continues on.

From this point on, the witch becomes little more than an observer for awhile, until the evening after Howl shows Sophie a secret garden. As Sophie helps the Witch into bed, the old woman remarks that Sophie seems to be in love, as she’s been rather quiet for awhile, deep in thought.

When Sophie inquires if the Witch of the Waste has ever been in love, she proclaims she still is. The Witch proclaims how she loves “strapping young men,” for both their hearts and appearances (leading Sophie to give a small look of disgust). She is also cognizant to recognize an air raid siren, and is sure Suliman’s henchmen are looking for where they are.

When Sophie’s mother visits during this time, the Witch becomes a little more active. Opening a draw-string bag Sophie’s mother brought, the witch finds ‘a tracking bug,’ and tosses it to Calcifer to burn up…but it instead, does not agree with his digestion. She also finds a cigar, which she soon takes to smoking. This also seems to make her come alive more, claiming the smoking of the cigar as a “pleasure,” when Sophie wishes her to put it out.

When Howl returns to the house during an aerial raid, both he and the Witch share a small conversation. While she shows slight interest that he has not attempted to run from her, Howl casually claims he’d like to keep talking, but has something else to tend to.

After the cigar is extinguished by Howl, the witch again reverts back to a quiet presence in the background, until Sophie and Calcifer take the moving castle to try and reach Howl. When Calcifer mentions how his powers would be stronger with Sophie’s eyes or her heart, this causes the Witch to perk up.

It is then that she realizes just where Howl’s heart is: it’s the source of where Calcifer is drawing his magic from (aka, the pulsating ‘lump’ that has been attached to Calcifer since we first met him!). This realization then causes the Witch to go for the heart, her greed getting the better of her, as she causes chaos by disturbing Calcifer’s concentration.

In her mad desire to ‘have Howl’s heart,’ it is only afterwards does she realize she has picked up a flaming object, but is unwilling to let go. Sophie then does the logical thing regarding a fire, and throws water on the Witch and Calcifer, whose flame dims to a soft blue!

This move ends up destroying the remnants of the castle, and what magic is left, sends a small portion still marching along, as the Witch laments that her ‘heart is ruined.’

The next time we see the witch, she, Markl, and the scarecrow Turnip Head, are seen atop a wooden flooring, being moved by two legs. As well, the Witch still has not let go of Howl’s heart.

Howl brings Sophie to them, before collapsing. Sophie realizes the only thing that will save Howl is his heart, but the Witch of the Waste is still unwilling to part from it, until Sophie embraces the Witch, pleading to have it back.

“You really want it that badly?” asks the Witch.

When Sophie responds with an affirmative, the old woman finally relents.

“Alright,” she says, handing it over, “But you better be prepared to take care of it.”

This becomes the Witch’s turning point. Though not as major as Howl’s, it is her way of letting go of an old obsession. Her speech to Sophie, almost sounds like she is willing to let this young woman, ‘have’ Howl’s love.

“Thank you,” responds Sophie, kissing the old woman, “you have a big heart.”

Miyazaki’s depictions of forgiveness and even kindness seem to be on a different plane than Western minds. Most people would have assumed Sophie would have held some form of grudge against the Witch of the Waste for all the grief and struggle she put her through. However, in this moment of helping, Sophie is willing to let this action be seen as a sign of apology.

Shortly after Howl’s heart is restored to him, he regains consciousness. As well, Sophie manages to break the curse on another of their comrades named Turnip Head, who it soon turns out, was the Prince, whose disappearance started the war.

The Witch of the Waste even manages to recommend he return to his kingdom quickly to end further fighting of the “ridiculous war.” She also gives him a wink, saying she looks forward to “his return.”

The final thing we see of the Witch of the Waste, is relaxing in a small garden in the newly-rebuilt Moving Castle. With her magic gone, she seems to have willingly settled into accepting both her age, and appearance…though if her comments to the Prince were any indication, she still has a penchant for handsome young men…proof that not all ‘curses’ can be broken with age and kindness.

__________

Jones’ story marked the first book adaptation Miyazaki had directed (the last one being Kiki’s Delivery Service almost 15 years before), and each time, he puts his own spin on the material, much the way Disney did with Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book.

This is definitely a change from the way the Witch of the Waste is portrayed in the original story. Though she was banished to the Wastes as mentioned in the film, she curses both Howl and Sophie, and even had plans to usurp the Kingdom, though in the end, Howl ended up killing her. As well, the curse placed upon the scarecrow (dubbed “Turnip Head” in the film), was also the Witch’s doing. But as is the way with Miyazaki’s adaptations, he has his own motivations for the characters and settings. Another example is the castle: Jone’s story depicted it as more of a ‘castle that floated on a cloud, as opposed to what Miyazaki concocted.

One could say that The Witch of the Waste’s “love” is not actually one of being genuine, but more of an obsession based on superficiality, almost a reflection of her own superficiality of keeping her appearance. She has no one she cares for except herself, and her own obsessions. However, it does feel that with the willing kindness that Sophie and the other members of the moving castle have shown her, she is willing to be adopted into this helter-skelter family, and has found a chance to move into a new turning point of her life, just as the others have begun to do.

*And thus concludes a trilogy of character observations in regards to “Howl’s Moving Castle.” I will admit that this post was largely due to a reader who claimed she really enjoyed reading my thoughts on these characters. I have several more regarding other Ghibli films, and I hope to continue to write them. Of all the different postings, I find these have been some of my most-viewed writings.*

Movie Review: The Tale of Princess Kaguya (Kaguyahime no monogatari)

Within the last year, much of the world was thrown into shock by two major announcements. One was the (supposed) retiring of Studio Ghibli co-founder, Hayao Miyazaki. The other shock came when rumor spread that the famed studio he was a part of, would most likely shut down…however, still continue to do small animated projects for Miyazaki’s Ghibli Museum, located in Tokyo.

However, buried within much of the back-and-forth of the internet, was the information that Ghibli‘s other co-founder, Isao Takahata, was releasing his first animated feature in over 14 years: The Tale of Princess Kaguya (Kaguyahime no monogatari). The film saw release in Japan during the Fall of 2013, and has just reached American shores, as of October, 2014, for a limited theatrical release.

Of the directorial co-founders, Takahata is a less constant than Miyazaki. Since the founding of the studio in 1985, he has only made 5 feature films, including Kaguya. However, each time he releases a film, each one tends to be something special in its own right. Many highly praised his 1988 film Grave of the Fireflies, and one that I found myself appreciating very much ,was his 1991 release, Only Yesterday (of which I discussed in one of my postings here ).

__________

The story of Princess Kaguya, is based on the 10th century Japanese folktale, The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter. Though often changed over the centuries, the central storyline consists of a man who finds a baby within a bamboo stalk. As he and his wife were childless, they happily welcomed the little babe into their lives. As the man cut down more bamboo trees, he found riches within them, and took this as a sign that the girl was a Princess. And thus, decided that she must be raised as one.

Takahata keeps much of the tale’s origin woven into his own tapestry on-screen, but does add his own embellishments to the story. He develops a number of characters within the tale, as well as adds his own.

Kaguya herself is a wonderful character within the film, one who seems to thrive amid the country where she is born into, as well as in the company of a gang of village children who live near her parents’ hut.

This is highly contrasted when she is to begin her life within the confined walls of the city, as her father wishes. At first, being in this new and exciting world is fun to the Princess, but she soon longs for the tranquility she grew up in. We see her find little pockets of happiness here and there, but there are times when she seems to quietly find herself wondering about things. In a weird way, Princess Kaguya almost reminded me of another famous humble beginnings film character. I speak of course, of Charles Foster Kane, from Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane.

I can see some possibly taking issue with Kaguya’s placement in this society, but one must remember, it’s not a world that is being run through with modern-day popular-culture or the ‘girl-power’ of films like Brave or Frozen. It shows the sometimes sad realities and sometimes ridiculousness of some past traditions. There does come a moment where Kaguya balks at having her eyebrows plucked and blackening her teeth as part of a traditional dressing, but does so out of obligation to her parents. One gets the impression that she feels an obligation and a familial love towards them, but she is also wrestling with her inner emotions…and possibly, something else?

With his 2000 release My Neighbors the Yamadas, Takahata sought to emulate a style similar to the comic strip the film was based on, giving that film a sketchy, watercolor feel. Kaguya almost captures the same feeling, but moreso in a historical context. Much of the style and characters take their cues from the Edo period of Japanese culture and art, though ‘simplified’ into a world of white backgrounds, watercolor, and pencil lines.

Even still, the character of Kaguya is drawn differently from the others, looking more like a modern-day depiction of a woman than the Edo style of the 17th century. There’s a great contrast played up when she is put next to Lady Sagami, who is her tutor in how to properly be a Princess (as seen in the image below).

Much like Miyazaki, Takahata seems to find a way to bring nature into his film, setting it up with a contrast at times to the modern city (of the time). Much like how the world seems to ‘breathe’ in natural beauty, Kaguya almost does the same. Her youth becomes one of fun memories, and her yearnings for return to that past world, keeps coming back to her, often in emotional ways that seemed to seep into the audience around me.

Unlike most filmmakers, Takahata chooses a different composer for each of his films. This time, the honor falls to Jo Hisaishi, Miyazaki’s musical collaborator. And just as can be expected, Jo doesn’t disappoint. Traditional instruments are used in a number of pieces, but much like the Princess herself, Hisashi’s score finds itself hitting a number of emotional areas. In one scene, he utilizes strings with a striking of the piano keys, to get down a major moment for the Princess. And in an interesting contrast, a celebration theme is almost cause for the opposite of the moment. I’ve yet to hear a Hisaishi score I didn’t like, and this is one that fans should pick up, if they haven’t yet.

__________

Watching the flow of the characters on many unfinished backgrounds, put me in mind of another release from the previous year, the French animated film, Ernest and Celestine. Both are wonderful adaptations of some interesting source material, and the simplicity of their art is the kind of thing that I could see inspiring many to pick up a pencil. heck, I kept watching the flow of Kaguya’s hair, just admiring the line work.

Every year, I always hope for one animated feature to rip my heart out, as well as find a film that is incredibly good, but that the general public will never really embrace. This year, I’m surprised (and happy) to say, that both of those distinctions, are melded into The Tale of Princess Kaguya. There’s probably another 500 words I could have put down about the film, but I had to stop myself.

Though Takahata has not said anything about retirement, one has to assume that given his age (79, 6 years older than Miyazaki!), that this might just be his swan-song: a story from his country, brought to life in a flurry of pencil, watercolor, and emotion. The Wind Rises was moreso like Miyazaki (in the spirt of that film’s lead), holding his head high, and walking stoically into the sunset. With Princess Kaguya, Takahata is willing to show (or remind) us that even if he may not have had his head in the clouds like his friend, he still managed to be both grounded at times, yet emotionally appealing, in ways that not many may comprehend. One can only hope that maybe, those that are touched by his latest film, might be able to seek out his other works, and see what they’re missing.*

*Blogger’s note: Isao Takahata’s film “Only Yesterday” is not available in the United States.

Movie Review: The Wind Rises

Growing up can be a funny thing. In the last 5-7 years, I had grown shocked when such popular animators like Andreas Dejas and Glen Keane took their leave from Walt Disney Feature Animation. And then in the fall of 2013, one of the most shocking proclamations was made: legendary Japanese animation director Hayao Miyazaki claimed he was retiring…for real, this time!

After almost a decade of saying each new animated feature film would be his last, Hayao finally admitted that The Wind Rises was truly the end of the road for him, marking his 11th directorial work…and also one that seemed a real departure from his previous works… in a manner of speaking.

Unlike his past works,The Wind Rises focuses on a real-life figure: Jiro Horkoshi. While that name means nothing to Western minds, Jiro was a renowned aircraft designer in Japan during the second World War. One of his biggest claims-to-fame, was the design of the Mitsubishi A6M Zero. In historical terms, it was these planes that would be instrumental in numerous attacks on Pacific targets, including Pearl Harbor.

Airplanes and flight have largely seemed a point of fascination for Hayao Miyazaki, as seen in the majority of his films. Along with crafting his own flying machines for many of his fantasy pictures, his 1992 production Porco Rosso, took place amid the European world in the 1930’s, with numerous aircraft playing big roles in its storyline. Needless to say, it almost feels like The Wind Rises shares some animated DNA with Porco.

In a dream during his childhood, Jiro encounters Italian aircraft designer, Caproni.

At the start of the film, Jiro is a young man who dreams of flying, but is frustrated that his near-sightedness means he won’t be able to soar above the clouds. It is in his own thoughts that he resolves to do the next best thing: if he cannot fly aircraft, he can design them. His dreams soon include famed Italian airplane designer, Gianni Caproni, after he has read about Caproni’s many works. Jiro soon becomes so enamored with the designer, that the two seem to “share” a dream, with the Italian giving Jiro guidance, and showing him aircraft that have not yet been built.

The overall film shows Jiro traverse across almost 30 years of his life, growing from a dreamy young boy, to an employee for the Mitsubishi Internal Combustion Engine Company Limited.

At work, Jiro is constantly being scrutinized by his diminutive boss, Kurokawa. Much like the character of Piccolo in Porco Rosso, much comedy is milked out of these situations, from Kurokawa’s constantly flapping hair, to his quick and snappy demands. Word was, some on the Studio Ghibli staff said the character reminded them of Miyazaki himself.

Jiro (left) shows his latest efforts to senior designer Hattori (center), and his boss, Kurokawa (right)

The process of the company’s airplane construction is also rather intriguing. Jiro’s friend Honjo tells how he wishes for them to develop airplanes that are as advanced as those in other corners of the world, but that by the time Japan has done so, newer innovations will keep them behind. Also as a show that the country is still behind, is that when it comes time to take their latest creations to be tested, a team of oxen are utilized to pull the aircraft.

In the film, Jiro is given the role of a man who seems to constantly be upright and in control of a situation, even when it seems to be falling apart. This may seem odd to some Western minds, but it is the concept of the film’s “hero” being in control that seems to be at work here. It could be that this is a way of Jiro thinking, “this didn’t work, but my greatest masterpiece will happen one day.” There’s a look and action about Jiro, that reminded me of Ashitaka in Princess Mononoke, and to a lesser extent, Haku from Spirited Away.

Naoko (left) and Jiro (right) make their way through a freak downpour.

The one concept that has never really been a big part of Miyazaki’s films, has been romance. Or if there is, it’s usually been very subdued. However, the use of it within Rises becomes something that feels rushed, and rather implausible. The meeting between Jiro and Naoko Satomi has its moments, but unlike some of the stronger female characters we’ve seen Miyazaki give us in the past, she comes off as more of a prop to Jiro’s story. While the real-life Jiro did marry in his lifetime, the character of Naoko is largely fabricated. It’s possible she may have been created as a way to showcase the life of those in society outside of the factory walls.

It is also within the narrative structure of the film, that I found myself rather non-plussed. Japan has been known to do non-linear storytelling, but even in concepts like Spirited Away, and Howl’s Moving Castle, I was still able to not feel jarred as much from the story, as I was during Rises. It feels like the film could have been 3 hours long, but was truncated to only show certain highlights of Jiro’s career.

Another area that I found rather off-putting, was that I never really felt like I connected with many of the people that Jiro is surrounded by. The two most prominent characters that stood out to me, were Mr Kurokawa, and Jiro’s sister, Kayo. Maybe it was because they were two that seemed to get a little more ’emotional’ than some of the more subdued, extra characters. I was expecting maybe more interaction even with Jiro’s co-worker and University friend Honjo, but he seems almost as stoic and deep-in-thought as Jiro at times.

Naoko contemplates by a small pool.

Of course, one thing we cannot discount, is that the tradition of painterly stylings by Studio Ghibli is alive and well in this latest feature. While the film relies once again on computer technology, much of the vehicular flight and movement appears to have largely been achieved by hand. Even in one scene, where smoke is released from a series of plane engines, it curls and swoops in graceful ways that computer simulations can’t replicate.

In each of his films, there seems to be an element that Miyazaki chooses to do differently from his other works, and in Rises, it becomes a notion of sound. Much of the sound of the airplanes we see, are comprised of human vocals making noise. This even seems to carry over into one of the most eye-opening sequences, when Jiro finds himself in part of 1923’s Great Kanto Earthquake. The sound of the event is one of a heavy-breathing, almost visceral human voice. Even in the eventual aftershocks, the Earth seems to ‘breathe’ like that of an angered being.

In the last few years, Studio Ghibli has given itself over to films that seem more real than fantasy. 2011’s From Up On Poppy Hill is almost completely devoid of these flights of fancy, and The Wind Rises also seems to be going down a more ‘mature’ path. Even so, Hayao’s swansong seems a little more “humble” next to his greatest works like Princess Mononoke, or Spirited Away. In a sense, it almost feels like a last great experiment, much in the same vein as Ponyo (which was done without the use of computers).

The real Jiro Horikoshi

In select cities, the film is being released in both an English-Dub, and a subtitled version, which is the first time since Spirited Away that one of Studio Ghibli’s films has had this happen. If you’re a fan of Hayao’s work, then I strongly recommend taking the time to see The Wind Rises. Though it isn’t as full of previous flights of fancy, there’s a finality to it that almost seems to gel with Miyazaki’s claims that his retirement this time is permanent…and if that is so, he can be credited as one of the few directors that was able to go out on decent note.

An Animated Dissection: Howl’s Moving Castle, Part 2 – Howl learns maturity

As I started writing about Sophie from Howl’s Moving Castle, I suddenly realized I was doing a great disservice by not analyzing another character who grows and changes in the film: Howl himself!

Though Howl’s outward appearance doesn’t make as major a change as Sophie does, it is his inner self that changes over the course of the film.

The village where Sophie lives has rumored about Howl for some time. Though noone seems to know exactly what the wizard looks like, Sophier’s co-workers at the hat shop tell how he’s interested in devouring the hearts of pretty young girls (even Sophie’s step-sister Lettie mentions this).

Our first appearance of Howl is as a handsome blonde-haired, blue-eyed young man. Though he doesn’t devour Sophie’s heart, one could say he has almost ‘stolen’ it, given how she seems in an unbelieving daze after their encounter.

Howl doesn’t reappear until after Sophie has been cursed, and finds her way into his moving castle. Though he does have an apprentice (a little boy named Markl), this doesn’t necessarily make Howl ‘mature.’ The castle is helter-skelter inside and out. Dust and cobwebs all over the place, not to mention books and bric-a-brac everywhere.

We soon find that Howl is also a fugitive of sorts: he uses multiple identities across different kingdoms, and different portals of entry to them. With a war going on, each of the kingdoms is recruiting wizards and witches to join in with their battles, but Howl does not take sides, preferring to stay neutral to the kingdom’s various affairs.

Using his magic powers, Howl turns himself into a winged creature, that seems to just pass through the battles, sometimes taking on some of the aircraft or wizards in small skirmishes. However, such use of power is slowly taking a toll on him. Calcifer mentions that the more times he goes into these battles, he loses himself to being unable to regain his human form. One could almost see this as Miyazaki’s way of saying that war can ‘change’ people, sometimes not for the better.

Sophie is one of the first to really make a change in Howl’s lifestyle (for the better). First intentionally (cleaning the entire castle), and then accidentally (messing with his potions in the bathroom). This results in Howl having a breakdown in vanity, when he shows her that his blonde hair has turned reddish-orange, before finally regaining his ‘natural’ black coloration.

In a surreal and dark scene, we see Howl lamenting that unless he’s beautiful, he has no point in living. This causes the room to twist and bend, and a green ‘goo’ permeates through his skin. Sophie considers this to be the equivalent of him ‘throwing a tantrum,’ but also shows how vain Howl has become.

When we next see Howl, he’s laying in bed (in his rather cluttered bedroom). His hair is still black, and from this point on, he doesn’t attempt to change its color again (a first step into accepting who he is, and moving into maturity).

After the ‘hair fiasco,’ we find out more regarding Howl’s immaturity. He tells Sophie about how he once was in love with the Witch of the Waste, but then when he found out she wasn’t beautiful, he left her. As well, he has not answered any of the summons by the different kingdoms in regards to their recruiting him for their side of the war.

Sophie recommends that Howl meet with at least one of the Kingdom’s rulers, and explain his own feelings in regards to the war. Howl feels that such a thing won’t deter the request for him to serve, when he hits on a ‘bright idea.’ He suggests that Sophie pretend to be his Mother, and get him out of his obligation with one of the kingdoms. Naturally, she sees this as just another way for him to avoid responsibility. When Howl sends her off, her expression and tone definitely make it clear that she is disappointed at his ‘solution,’ and is doing this ‘under protest.’

However, Howl gives her some consolation to this plan. Before she leaves, he slips a ring onto her finger, telling her that it will protect her, and that he’ll be following her in disguise.

Going to the Royal Palace of one of the kingdoms, Sophie has an audience with the King’s Royal Sorcerer, Madame Suliman. Suliman reveals to Sophie that Howl was once her most gifted student, one whose powers she felt could lead him to taking her position. However, his heart was ‘stolen’ by a demon, and he left his apprenticeship.

Suliman claims that Howl’s uses of magic now are purely for selfish reasons, and that without a heart, he may soon be unable to control his powers. This is some nice insight into the powers Howl has, as well as the thought that demons exist in this world, and can corrupt the magic of some users.

Eventually, Howl shows up in disguise, attempting to retrieve Sophie. However, his disguise is seen through by Suliman, and she uses her powers to make Howl’s powers manifest. Without his heart, Suliman’s powers bring forth the winged creature inside Howl.

Sophie manages to get through to Howl, causing him to regain focus, and escape with her and The Witch of the Waste (who had also been summoned by Suliman). Using a flying vehicle, Howl sends them back to the castle, while he disappears from sight.

After this, Howl returns late in the evening, transformed moreso into his winged creature form, and dripping blood. Sophie awakens and follows his trail, encountering Howl in a carved-out cave, embedded with toys and children’s things. At the end of them, she finds Howl transformed into a large, winged creature. She tells the winged Howl that she wants to help him, but is met with a response of “You’re too late,” before the creature disappears into darkness. A few moments later, it seems that the encounter was nothing more than a dream, but it may have given Sophie some clues to helping Howl.

Sophie then speaks with Calcifer the fire demon, regarding Howl. Calcifer and Sophie have a deal that if Calcifer’s curse is broken, he can break Sophie’s. However, neither is allowed (per the spells on them) to tell what needs to be done to break the spell. At this point, Sophie suspects that Calcifer was the demon who stole Howl’s heart. He is unable to say yes or no to her question, but when she inquires what would happen if Calcifer was extinguished, the fire demon mentions that Howl will die if he (Calcifer) dies.

Eventually, Howl reveals himself to everyone. He’s in good spirits, and informs his new ‘family’ (which now includes the true-aged Witch of the Waste) that they are moving to a new location, since the link to one of the kingdoms has been severed (to prevent Suliman from finding them).

The new place they move into is moreso a ‘home’ than anything else: in fact, it’s the former hat shop that Sophie once lived in! Howl has even included an extra bathroom, and has given Sophie her own room. It feels moreso like Howl is growing up, thinking of others. He even gives Sophie a little insight into his past, by taking her to a secret garden, allowing her access to come here whenever she wishes.

Howl’s new role as a family protector continues on, as he soon after goes away. The town is evacuated, but Sophie, Markl, and The Witch of the Waste stay behind. Howl patrols the skies, becoming more and more bird-like as the war draws closer.

When Howl finally does return to the new home, it is when it is threatened. Howl manages to stop a bomb from destroying the home, and attempts to help cleanse Calcifer of a deadly ‘tracking bug’ that was snuck into the house.

He then attempts to leave, but Sophie wants him to not fight, and come away with them to seek refuge within the castle (whose main location is situated on the outskirts of the town, away from the firefight). However, Howl claims that he won’t run anymore, and that he is committed to fighting to protect her and their ‘family.’

Unable to stop him from leaving them, Sophie has Markl, The Witch of the Waste, and Calcifer transferred into the castle. Going outside, she can see Howl tearing into one of the kingdom’s flying machines. From the distance, he looks like a roaring monster, most likely a side-effect that war has thoroughly unleashed his inner demons, pushing aside his humanity.